Functional Medicine

Functional Medicine

Type 1 Diabetes

Health risks associated with type 1 diabetes (an autoimmune disease!)

If you have recently been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes, you may have been shocked when the doctor began to explain that carbohydrates are not the enemy. We have an epidemic of type 2 diabetes that stresses limiting carbs. While several similarities exist between the two types, the causes, treatment, and symptoms can be different for someone with type 1 diabetes.

Medical risks and long-term complications for someone living with type 1 diabetes can severely reduce quality of life and even be life threatening. Monitoring your diabetes and adhering to a treatment plan is critical to limiting long-term damage that can occur over the years.

Health risks associated with type 1 diabetes

- Kidney Failure

- Edema

- Diabetic Nephropathy (a chronic disease affecting the kidneys)

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis (a life-threatening emergency from high ketones in the blood)

- Stroke

- Heart Disease

- Diabetic Retinopathy (damage to the retina of the eyes causing loss of vision and blindness)

- Glaucoma

- Blood Vessel Blockages Due to Cholesterol Plaques (Requiring Angioplasty/Stent Placement, Amputations, Or Bypass Operations)

- Diabetic Neuropathy (nerve damage)

Common symptoms of type 1 diabetes:

- Frequent Urination

- Excessive Thirst

- Excessive Hunger

- Extreme Fatigue

- Blurry Vision

- Slow Healing Wounds

- Unexplained Weight Loss

The differences between type 1 and type 2 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes is often referred to as juvenile diabetes due to the early age of onset for the majority of people diagnosed with it. It can, however, begin at any age. Type 1 Diabetes is an autoimmune disease that causes your body to attack the pancreas. The pancreas is the gland responsible for the production of insulin. The pancreas begins to atrophy and produces little to no insulin. A person with type 1 diabetes is insulin-dependent, meaning they require insulin injections to help move glucose into the cells. Body type tends to be slim.

Type 2 diabetes is very different from type 1 diabetes. With the rise in obesity and the decline in active lifestyles, type 2 diabetes has led to millions of new cases every year. Until recently, it was rarely seen in children, and it tended to occur more commonly in people over the age of 45. As it grows to epidemic proportions, young children and teens afflicted rises at alarming rates. In America, 90 – 95% of the cases of diabetes are type 2, where your body develops insulin resistance. In order to get the blood sugar into the cells, it requires more insulin. It is managed through a balanced diet, an active lifestyle and insulin.

Autoantibodies associated with type 1 diabetes

Type 1 diabetes is often overlooked as an autoimmune condition. But with its autoimmunity status, it carries early biomarkers that help make it more preventable. I discuss in detail how you can prevent, arrest and reverse autoimmune conditions in my book The Autoimmune Fix.

As type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune condition, the mechanism follows a predictable pattern. You start with a genetic predisposition, carrying the genetic codes from birth within your DNA. Then, you introduce environmental triggers, such as infections, antibiotics, and toxic burden. A cascade of events begins to occur. You eventually see a shift in your gut health from supportive to dysbiosis (an imbalance of healthy gut bacteria) which leads to intestinal permeability (leaky gut), which then sends inflammation throughout the body via the bloodstream. This triggers an autoimmune response such as islet cell autoantibodies. These target islet cells which include the Beta cells that produce insulin in your pancreas. This activates T-cells to destroy the Beta cells, making it progressively more difficult to produce insulin.

Several type 1 diabetes autoantibodies have been identified. These are antibodies that are attacking your own proteins, such as the islet autoantibodies. Others have also been identified, including those that target insulin, glutamic acid decarboxylase, tyrosine phosphatase, and the zinc transporter protein.

Testing for these autoantibodies prior to diagnosis may help prevent or delay the onset of type 1 diabetes. The Type 1 Diabetes Self Care Manual written by Doctor’s Jamie Wood and Anne Peters reported that “in a recent study, 98% of people with recently diagnosed type 1 diabetes tested positive for at least one of these autoantibodies.”

They further state, “Studies suggest that people without diabetes who test positive for two or more type 1 diabetes autoantibodies have between a 27% and 80% risk of developing the disease over 5 years. For those with only a single autoantibody, the risk drops to 5%.”

The rise of blood sugar

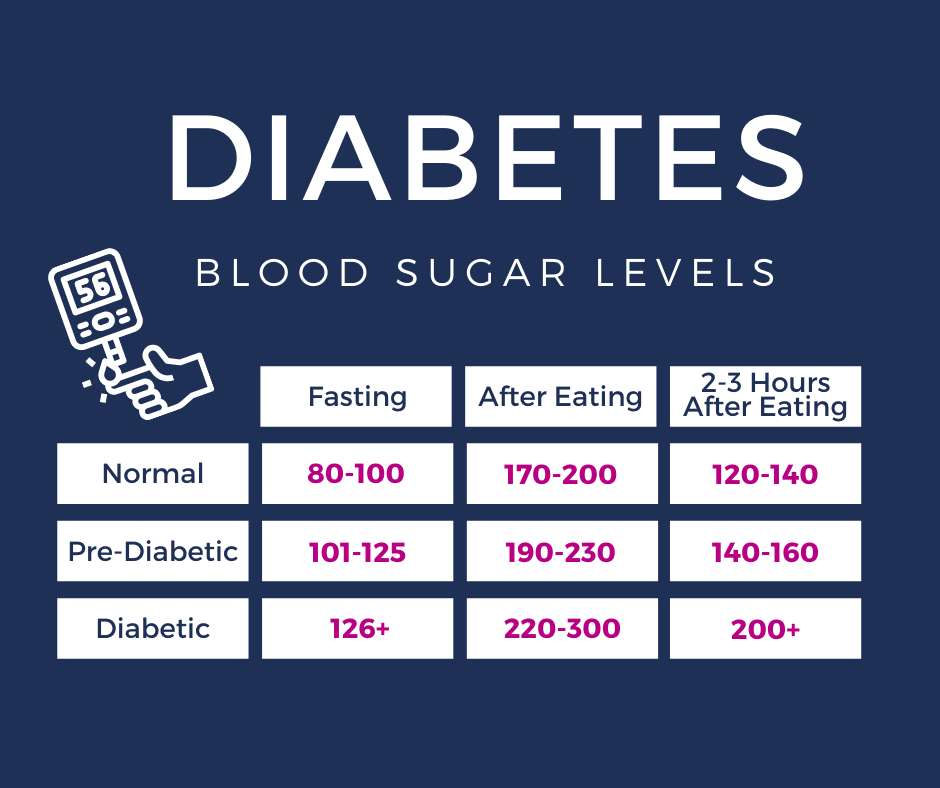

As your body consumes food without the necessary insulin to get the blood sugar into the cells where they can be utilized, your blood sugar levels rise.

Your glucose levels change throughout the day. When you haven’t eaten for a long time, it drops. If it drops quickly or too low, you may feel faint or dizzy. This is your body’s alert system warns you that it needs food now.

When you eat, your blood sugar begins to rise. Insulin is produced to help transport that blood glucose into the cells where the glucose can be utilized.

Depending on the food or drink consumed, this can be a quick bolt to the system if the food has a high glycemic index, or it can be a slow and steady gradual rise if the food has a low glycemic index. Foods with high glycemic index notoriously give you that sugar crash. You eat, and 20 minutes later you feel tired.

As the blood sugar is received into the cells over time, the glucose levels in your blood go back down.

The delivery of blood sugar

Imagine you are on a loading dock unloading a truck filled with boxes. As you unload those boxes (glucose), you place the boxes one by one onto a conveyor belt (your bloodstream). The amount on the conveyor belt rises. A person (insulin) then moves the boxes from the conveyor belt to where they will be stored (the cells). The more boxes there are, the more people will be needed to move them.

Now imagine you have a slow and steady pace. You aren’t in a hurry. You have all day to unload the truck. The items are light and easily moved, and there are plenty of people to help. This is what it is like inside your body when you are having foods with a low glycemic index. They are absorbed slowly over time. There is no sudden surge of blood sugar, so the levels slowly and gradually rise very little.

Now imagine it is the holiday season, and someone calls off work. You have a lot of boxes and not enough people. Everyone is working overtime to get the job done. This is a little like high glycemic foods in the body. While necessary for life, insulin is highly inflammatory. Your pancreas is pumping out the insulin causing a lot of stress on your body. So, you work hard — then crash.

For someone with type 2 diabetes, those low glycemic foods are critical to managing their diabetes through proper diet. However, for someone with type 1 diabetes, those high glycemic foods can at times be lifesaving.

Who said you don’t use math when you get older? Tell that to a diabetic!

For type 1 diabetes, an endocrinologist works with you to determine which insulins are best to keep your blood sugar numbers within the ideal ranges. After some initial experimenting, the dosing is determined. There are four different types of insulin.

Long Acting – This type works throughout the day and night (approximately 24 hours) working to maintain a low blood sugar.

Intermediate-acting insulin (NPH insulin) – This type of insulin is often used in conjunction with a short acting insulin. Depending on the insulin, it can take up to 4 hours to work fully. It peaks anywhere from 4 to 12 hours, and its effects can last for up to 18 hours

Regular or short-acting insulin – This type is usually taken prior to meals as it takes about 30 minutes to work. It lasts about 3 to 6 hours in the system.

Rapid-acting insulin – This is the fastest acting insulin. It is generally taken right around the time you are ready to eat in order to keep blood sugar numbers from rising. It also works for the shortest period of time, lasting only about 2 to 3 hours.

Here’s where the math comes in…

You have a basal dose and a bolus dose. A basal dose refers to a low, continuous dosage of insulin. This dose gives you a baseline amount needed to sustain throughout the day.

When you eat, you need to supplement that dosage with a bolus dosage. This is the injection you give yourself in order to raise the level of insulin in your blood to meet the demands of the incoming food.

Every time you eat, you need to adjust for the amount of carbs that you calculate will be in the meal. Let’s say that for every 15 grams of carbohydrates, you need to bolus one unit. You estimate that the meal you are about the eat has 45 carbohydrates. You enter the number of carbohydrates and divide it by the number of carbohydrates per unit. (In this case 1:15.)

45 carbs ÷ 15 carbs/unit = 3 units

So, before you would eat your meal, you would bolus 3 units in order to account for the carbohydrates you will be eating.

However, if your basal dose is set too high, you would need to adjust the bolus amount lower. This is why I say there is a little experimentation initially. You want to find the right basal amount that doesn’t make you overcorrect. You want your numbers steady, not up and down.

If you bolus too much, your blood sugar levels will drop too much. If you have too high a basal dose, your blood sugar levels will be dropping throughout the day.

Conversely, if you underestimate the amount of carbohydrates and bolus too little, or your basal dose is set too low, your blood sugar levels will rise too high.

Routine testing for someone with type 1 diabetes

A simple finger prick test can gauge whether your numbers are falling within the desired range on a day-to-day basis. A blood test for your A1C level gives a bigger picture of how well you are consistently doing.

A normal A1C level is 5.6 percent or below. A level of 5.7 to 6.4 percent indicates pre-diabetes. People diagnosed with diabetes have an A1C level of 6.5 percent or above.

An endocrinologist will work with you to help you set appropriate health goals, such as set a target A1C and determine the appropriate dosing for you. A diabetes educator or a nutritionist can assist you in learning the basics in nutrition to help you make those calculations.

Should you avoid carbs? Absolutely not. You need them. Just choose healthy carbs.

What about gluten?

There is a close association between type 1 diabetes and celiac disease. Among one of the most frequently associated autoimmune disorders with celiac is type 1 diabetes.

The presence of celiac disease in type I diabetes is approximately twenty-times higher than in the general population.

The removal of gluten has been a successful component in the treatment and prevention of autoimmune conditions. In addition, strict adherence to a gluten-free diet is a requirement in managing celiac disease.

Study shows improvement in insulin secretion following a gluten-free diet

Autoimmune disorders occur 10 times more commonly in people with celiac disease than in the general population. One study examined whether a gluten-free diet could reduce autoimmunity in human preclinical type 1 diabetes.

Subjects in the study ate 6 months gluten-free, followed by 6 months of a normal diet containing gluten. Homeostasis model assessment-estimated insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) after the first 6 months of gluten deprivation decreased in 9 out of 14 participants. During the following 6-month period of a normal diet, HOMA-IR increased in 11 out of 13 subjects when tested at 6-month and 12-month intervals. Following the 6 months of a normal diet, one subject developed diabetes, and all of the others showed a decline of insulin secretion.

The study indicates that “removal of gluten from the diet over a period of 6 months cannot significantly influence the humoral autoimmune response in relatives at high risk for type 1 diabetes, but may have a beneficial effect on insulin secretion.”

What’s your trigger?

Remember that your genes don’t imply that certain medical conditions are your fate. You could be born with the voice of an angel, and if you don’t do anything to make it a career, you’ll never be a famous singer. It’s what you do with those genes that matter.

Prevention is always your best friend, and testing is one of the best tools you can use to determine whether your body is reacting to something in your environment.

For you it may be gluten, for another person it might be mold. But if you are on the autoimmune spectrum, it’s time to get serious and prevent future problems. Discover what your trigger is and eliminate it immediately.

REFERENCES

theDr.com. (n.d.) Type 1 diabetes. https://thedr.com/type-1-diabetes/

By

By